Recently I took part in a podcast where I was asked, “what is the most important factor for recovery?” While optimal physical recovery is certainly multi-faceted, what domain might be the most important? Nutrition? Stretching? How about an ice bath following a massage…or a proper aerobic cool-down? My unequivocal answer was SLEEP.

Sleep and hormones

We know that during deep non-REM sleep cycles, the body produces its highest levels of anabolic recovery hormones, such as testosterone, growth hormone, and insulin-growth factor. These hormones increase hypertrophy (muscle growth)and protein synthesis, while also increasing lipolytic activity(fat-burning) at rest. A drop in anabolic hormone secretion leads to impaired recovery and rebuilding of muscle, tendon, and bone remodeling in the body. In fact, three consecutive days of NREM (slow wave) sleep deficit can cut TT levels in half! When considering hormone release, one could infer that sleep quality is more important than sleep quantity; however, both factors are crucial.

Rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep is critically important for remodeling and recovery in the brain, and a deficit in this type of sleep negatively affects fine motor skills, decision making, reaction time, and concentration. It can also reduce memory, learning capacity, and even lower a person’s pain threshold and time to exhaustion.

Furthermore, a lack of sleep increases adrenal (stress) hormones such as cortisol that inhibit muscle growth. Poor sleep also influence hormones like ghrelin and leptin, which act to increase hunger and reduces satiety signals (full stomach feeling). Some metabolic problems caused by lack of sleep occur because the brain craves fat and sugar when sleepy – further leading to excess weight gain. Further investigations of sleep deprivation reveal increased risk for obesity, Type II diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, Alzheimer’s disease, osteoporosis, depression, compromised immunity, and even multiple types of cancers.

. A few more ‘eye-opening’ facts about sleep deficits:

- Studies have shown that sleep deprived people even show delays in showing, interpreting emotion; non-verbal skills that researchers believe to make up 65% of all communication.

- After 21 hours without sleep, task performance is worse than when legally drunk (0.08 BAC).

- Research has shown the same beta-amyloid plaques in the brain present with sleep deprivation (consistent 6 hours/night or less*) similar to dementia, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease.

*Significant detrimental effects with just one night (<5 hours) or 3+ nights (<6) hours of sleep

Sleep and Exercise

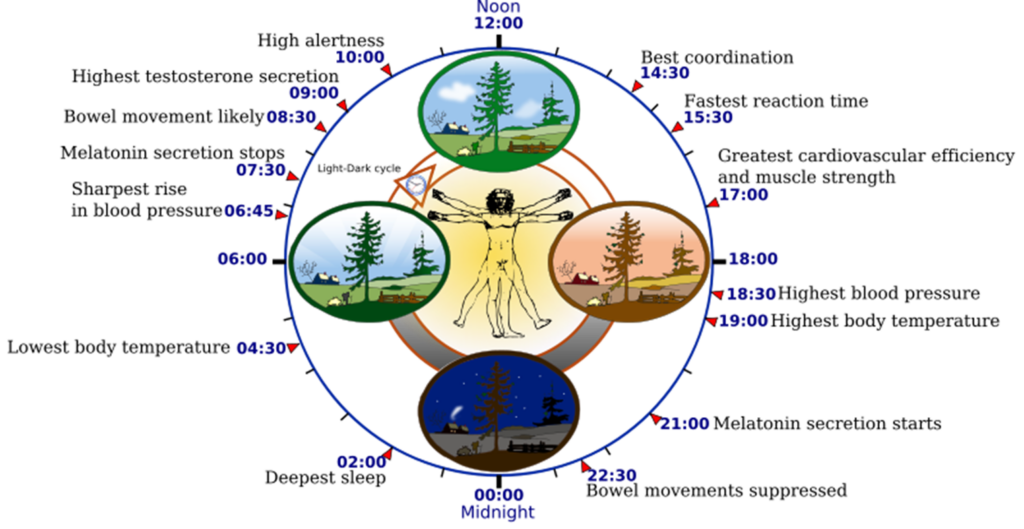

Many people know that the body’s natural circadian rhythm is dictated by the rising and setting of the sun. But fewer may realize that our bodies reach their maximum physiological readiness in the afternoon hours – sometime between 2 and 7 pm – with peaks in coordination, muscle strength and temperature, blood pressure, optimal cardiovascular efficiency and reaction time.

For years I have been dumbfounded as to why many groups of athletes and tactical operators prefer early morning training sessions – which tend to show up to an 80% increase in catabolic stress hormones compared to exercise at other times! Many use highly caffeinated products like pre-workout or energy drinks just to survive these zero-dark-thirty workouts; which acts to further increase epinephrine and catecholamines, leading to accelerated glycogen depletion and blood lactate accumulation…not to mention an increased injury risk due from dehydration.

Exercise later in the day is most effective for increasing overall daily testosterone production, and can almost create a ‘second spike’ in anabolic hormone levels. For those morning larks who sometimes experience an afternoon lull with energy, I would advise using short “powernaps” – which have also been found to boost anabolic hormone release along with a rejuvenation in both physical and mental energy. Coaches should remember that progressive overload always involves some continuum of fatigue, heavy training periods or loads should NOT be initiated if a chronic lack of sleep is suspected. This can quickly lead to overtraining or overuse injury.

It is important to realize that these risks are not just limited to the gym. Early work start times also lead to a sharp rise in emergencies during the afternoon ‘danger window’ (including drowsy driving fatalities or accidents operating dangerous machinery. In fact, each year there is a predictable spike in accidents and ER admissions during the ‘spring forward’ shift in daylight saving times – when people are robbed of just one hour of sleep at night!

Not long ago I experienced my own health scare after a chronic lack of sleep due to an early morning work schedule. In my case it was a very severe case of Bell’s palsy, which took nearly nine months to fully recover from. I realize that even though we can exercise common sense and listen to our own bodies, we may not always be in complete control of our exercise or work schedules. Therefore it can also be good to practice good sleep hygiene in the evening hours leading up to bedtime. A full list of some of these sleep hygiene tips (as well as things to avoid) will be included in my next blog! – CHRIS BORGARD

References

Short sleep duration is associated with a wide variety of medical conditions among U.S. military service members. Knapik et al, Sleep Medicine; January 2023.

Increased Risk of Upper Respiratory Infection in Military Recruits Who Report Sleeping Less than 6 Hours Per Night. Wentz et al, Military Medicine; 2018.

Augmenting hippocampal-prefrontal neuronal synchrony during sleep enhances memory consolidation in humans. Geva-Sagiv et. al, Nature Neuroscience; Aug 2021.

Sleep and Association with Cardiovascular Risk Among Midwestern U.S. Firefighters. Cabrera et al, Frontiers in Endocrinology; Nov 2021.

The Effects of Sleep Extension on the Athletic Performance of Collegiate Basketball Players. Mah et al, Sleep Research Society; July 2011.

Age Related Changes in Slow-wave sleep, REM sleep and Relationship with GH & Cortisol Levels in Healthy Men. Von Cauter et al, JAMA; 2000.

Shift Work and Sleep Quality among Urban Police Officers. Fekedulegn et al, J Occup Environ Med; March 2016.